Savannah and the water

Water Teachings, a workshop we held in May 2021, sparked many conversations. Here is one, with Savannah Walling, Co-Director of Vancouver Moving Theatre

How do you connect with water, where you live?

I live on a spit of land bounded by Burrard Inlet on the North, by the former tidal flats of False Creek on the south, and by filled-in tidal streams on the east and west. It’s called the Downtown Eastside.

I walk a lot – if you know the access points, you can travel through much of the downtown and eastside waterfront. This is my neighbourhood. After a rain, there’s a pond that accumulates, in Strathcona Gardens. It evaporates and comes back and evaporates as the rains come and go. Nearby, alongside a tiny garden pool, there was a statue of the Buddha; that’s gone now, but the memory lingers.

There are places where the land sinks, where I think “there go the underground streams”. Dips in the land, implying changes over time; I wonder often about the water lines underneath us: what is hidden and covered by concrete, and I feel drawn to uncover them. Many others share this desire- there has been a lot of community work to daylight streams covered over in areas out beyond False Creek.

On the waterfront near where I live is Crab Park at Portside, down at the foot of Main Street. I walk there often and remember its history. Determined to get waterfront access for the inner city, Don Larson, the Create A Real Available Beach Committee (CRAB) and their allies lobbied for years, camped out on the water front and built community support. Against all odds they succeeded and the 7-acre waterfront park opened in 1987. (But there’s still insufficient wheelchair access.)

After the 9/11 attacks in the USA, access to all the rest of our neighbourhood’s working waterfront was closed to the public- a great loss. Today community members, the Vancouver City Council and allies are lobbying for a cultural healing centre at Crab Park. The Union of BC Indian chiefs call Crab Park a sacred site of great spiritual and cultural significance for Indigenous people. Crab Park at Portside is under federal jurisdiction and plans for a cultural healing centre are waiting on approval from the Metro Port Authority.

I don't know if it is safe to swim at Crab Park due to all the marine pollution. So, I don’t wade in its waters.

People in our neighborhood have fought hard for Crab Park and access to the waterfront. They’re still fighting to preserve the park. And they’re fighting for a cultural healing centre.

I think about how Coast Salish nation is canoe culture – and the value of Crab Park waterfront as an embarkation and ceremonial landing point for generations to come.

I like to watch the water, the waves, and the birdlife – the gulls and geese, crows and eagles – I go over to sit by the heliport, for a view of the north shore and mountains, unimpeded by the super-sized ship-to-shore container cranes that interfere with views from Crab Park.

I also like to be out on the water, so I’ll take the Seabus (enclosed, alas) across the narrows. I walk the waterfront and along the north shore Spirit Trail. Even further east, out past Maplewood tidal flats, there’s a strong presence of river water and saltwater. I have so much respect for the activism, commitment and leadership of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation in caring for our waters. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation recently signed an Environmental Stewardship Agreement with Canada for Burrard Inlet with the intention to maintain all our communities’ connections to waters of this territory...

Can you give us a feel for waterfront and canoe culture as you experience it?

Since time immemorial, here on the edge of the Salish Sea, Salish people have hunted, fished, gathered resources, and welcomed visitors from their canoes on these lands and waters. Although canoe culture diminished as immigrant settlements spread, it never diminished. Since the 1980s, Indigenous people up and down the coast from Alaska south to Washington, have been reviving the ancient tradition of ocean-going canoes. I have witnessed two canoe landings with protocol in Crab Park.

Since 2001, Pulling Together Canoe Journeys have visited over 100 First Nations, travelling the traditional waterways, and building relationships that grow beyond the canoe journey. For almost 20 years, police and government public agencies have partnered with First Nations communities with a focus on youth. Each year's journey is hosted by a different nation, reconnecting youth to their culture...

In 2019, I was invited to travel on a Pulling Together Canoe Journey hosted by the Tla'amin Nation in Powell River involving 300 participants. The invitation came about because of a partnership with the Vancouver Police Museum and Pulling Together Canoe Society (which requires all partners to send a representative on a canoe journey before entering into agreement.) On this journey, I experienced the power that unfolds when people of many ages, ancestries, cultures, and lived experiences pull together for a common purpose. I’ve come to realize that the Downtown Eastside Heart of the City Festival has served as our community’s canoe: pulling together peoples of many ages, cultures, ancestries, and lived experience to express voices, art forms, and values of the Downtown Eastside.

At the 2019 DTES Heart of the City Festival, we co-presented a mini-canoe landing with protocol by Pulling Together canoe families. This was intended to lead up to a 20th-anniversary event of the Pulling Together Canoe Society (at the 20210 festival) with a larger landing of canoe families and an exhibit at the police museum on the history of the journeys.

Is it happening this year in Heart of the City?

Unfortunately, all this has been side-lined by COVID, and we don't know when or if the planned event might happen. The big Pulling Together canoe journeys involving hundreds of participants have not yet resumed.

Bob Baker and Wes Nahanee of the Squamish Nation have dedicated their lives to the resurgence of canoe culture. Both participated, along with Spakwus Slulum Dancers and Git Hayetsk dancers, in the 2012 production of “Storyweaving”, produced by Vancouver Moving Theatre in partnership with the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre. (Wes was also a steersman on the Pulling Together canoe journey of 2019).

In Storyweaving (directed by Renae Morriseau), Renae, Rosemary Georgeson and myself twined together stories, poems and personal memories with oral histories woven from cultural teachings, indigenous languages, protocols of canoe culture, the spiritual construct of the Medicine Wheel, West Coast dances, Aboriginal songs, western theatre practice and the ancient bone game of slahal.

Both Bob and Wes continued their involvement in events co-produced by VMT. Wes carved one of the Welcome Posts in Oppenheimer Park. Bob Baker participated in The Big House, the TRACKS Symposium, and the cultural sharings partnership with the Firehall Arts Centre In the Beginning and Openings.

At this year’s Heart of the City Festival, Bob participated in the closing ceremony for the physical and cultural refurbishment of the Survivors Totem Pole (at Pigeon Park), and as part of the launch of Honouring Our Grandmothers Healing Journey led by the Further We Rise Indigenous Artists Collective.

When you think of water, what comes up?

The movement of water. I grew up in Oklahoma; as a child I loved to watch the grasslands, and the wind blowing endlessly through the wild grasses, rippling them like waves of the sea.

Lately, when I think about water, I remember the names Savannah Tennessee that I carry from my great grandmother. She carried the names of rivers - the Savannah and Tennessee Rivers.

They weren’t the names I started with. At a Richard Schechner workshop (when New York City’s Performance Group visited UBC 48 years ago) we were doing a talking circle exercise and invited to use a name of our choice. I took my great-grandmother’s name and felt like I’d come home to myself. My grandparents were delighted at this link with the past (my parents puzzled but willing).

I’ve since learned that the name ‘Savannah’ – meaning a large expanse of grassland - comes from the Taino language spoken by the Indigenous people of the Caribbean when the Spaniards arrived in the 1400s. Over 300 years later, my great-great-grandfather said that Savannah Tennessee was the prettiest place he ever saw. He named his daughter for this place. A town? The river? A bay? We never knew. I think about the ancient Cherokee city of Tenasi – the place for which the Tennessee River and the state of Tennessee were named – and how it was drowned deep underwater by the building of the Tellico Dam. My great grandmother Savannah Tennessee and her husband Croel Walling obtained a farm after the US federal government forcibly “opened up” the Comanche Kiowa Apache lands for a homesteaders’ lottery in Indian Territory (known today as Oklahoma) This was a land of rolling buffalo wallows, depressions that held rainwater after runoff. In the next generation, the Walling farm was taken by the city of Lawon in a forced sale; today the farm lies under the waters of man-made Lake Ellesworth.

When you carry an ancestral name, what are the responsibilities and legacies that you inherit? For me, it’s a lifetime journey to understand my names.

I also have received the name hl Gat’saa, which means “supporter of all things.” Last summer, my husband Terry Hunter and I were adopted by carver Bernie Skundaal Williams into the st’langng 7lanaas Haida clan. We’re told that discussion and mentoring of us preceded the decision to adopt us. We understand that the adoption is linked to our history of getting things done in the Downtown Eastside and our history of support for indigenous-led projects such as the Survivors Totem Pole, a thousand-year old pole carved Bernie Skundaal Williams and raised in 2016 with protocols of the land at Pigeon Park, Carrall and Hastings Streets.

We understand the adoption journey carries responsibilities that will unfold over time. For Terry and myself, a primary responsibility is to help support Indigenous presence in the Downtown Eastside.

You have been working where art and social action transect for a long while. Can you mention some things that inspire you?

Here’s a quote that stays with me:

Cathy has been working for 20 years in Enderby/Grindrod in Secwpemc traditional territory of the Splatsin First nation. She created the big Enderby community play that inspired our DTES community to create a DTES community play, back in 2003. Her work has expanded into many large community-based projects. For the last few years, she's been exploring her relationship to the land through where food comes from, where the water goes, and through developing a sense of time based on natural indicators specific to the place.

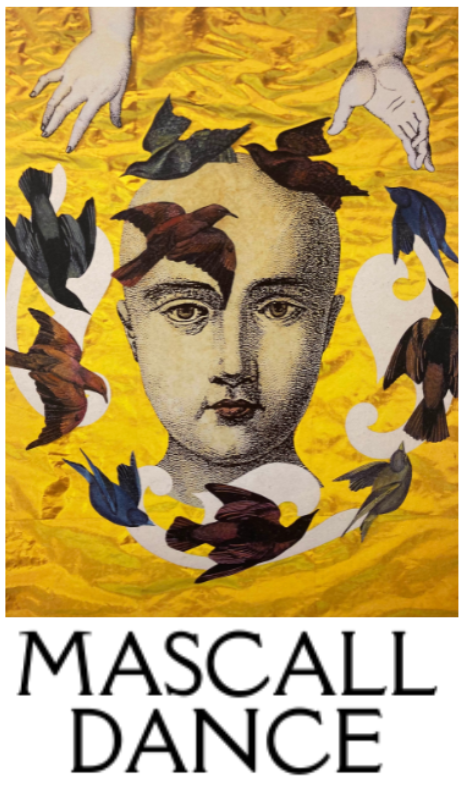

Cathy Stubington, Ruth Howard, Karen Jamieson, Renae Morriseau, Rosemary Georgeson, Marie Clements, Margo Kane, David Diamond, John Endo Greenaway, Powell Street Festival, and Vines Festival are among the many artists whose practice has inspired and amazed me over the years. As has been the unfolding and winding journey of Jennifer (Mascall)'s practice.

I am cautious around the benefits of concepts like ‘social action and art’. Everything depends upon the artists’ intention. Hitler was a visual artist and orator. Goebbels was a writer. Art is no preventative or magic cure for fascism, anti-Semitism, or systemic racism.

On my artistic life journey, I seem to have been led by the path I walk to this destiny: art engaging with community – many communities – learning, absorbing, witnessing, growing, informed by the way itself, and inspired by collaborators and mentors I meet along the way.